研究業績

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 日本が目指すべき社会的養護における制度と実践の座標軸の検証:5か国比較からの考察 | 科研費(基盤研究A) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 里親支援ソーシャルワークの構成要素に関する研究 | 科研費(国際共同研究強化A) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 里親不調による委託解除を予防する里親子支援モデル構築 | 科研費(基盤研究B) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 里親家庭における養育実態と支援ニーズに関する調査研究事業 | 「子ども・子育て支援推進調査研究事業」(厚生労働省) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 里親支援にかかる効果的な実践に関する調査研究事業 | 「子ども・子育て支援推進調査研究事業」(厚生労働省) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 措置変更ケースにおける支援内容や配慮事項に関する調査研究事業 | 「子ども・子育て支援推進調査研究事業」(厚生労働省) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 日本における「里親支援体制の近未来像」の構築~里親・施設・行政の有機的連携~ | 科研費(基盤研究C) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 児童養護施設からの家庭復帰ケースへの養育支援における市町村と施設との連携に関する研究~養育支援訪問事業と施設職員によるアフターケアとの有機的連携~ | 財団法人こども未来財団児童関連サービス調査研究事業 |

| 社会的養護施設における小規模化・地域分散化に対する意識・実態調査 | 神戸市社会的養護調査研究事業 |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 児童養護におけるアフターケア-その援助概念と方法の検討 | 科研費(若手研究B) |

| 研究タイトル | 研究費の種類 |

| 児童養護施設小規模ケアにおける環境設定のあり方に関する研究 | 科研費(若手研究B) |

チーム研究の部屋

2018年度から「チーム伊藤班」として、

きっかけは、2016年度にカナダ(ケベック)

2022年度からは科研費(基盤研究A)として、アメリカ、

The construction of the Foster family support model to prevent the cancellation of placement

In the majority of developed countries, children who are abused, neglected or cannot live with their parents for other reasons, are placed in foster homes. Japanese social foster care has traditionally been centred around institutional care. This led to the United Nations making recommendations for improvement and in response, Japan announced ‘The Issues and Future Vision of Social Foster Care’ in 2011 and a ‘New Vision of Social Foster Care’ to increase the foster parent placement rate in 2017. Professor Kayoko Ito, from the Faculty of Social Welfare and Education at Osaka Prefecture University in Japan, has assembled a team of researchers to work on a project that seeks to build a system for supporting foster parents and promote home-based care by foster parents. The intention is that this system will eliminate the burden of raising a foster child and thereby reduce the incidence of giving up, resulting in an overall improvement in foster care in Japan.

Children placed in foster care due to care breakdown

1. Introduction

For many years now, social foster care in Japan has been developed mainly in institutional care. However, the revised Child Welfare Law, which came into effect in 2017, has indicated that when considering where to place children in social foster care, priority should be given to “options that can provide a nurturing environment closer to home”. In addition, in the “New Vision for Social Care” announced in August 2017, one of the goals was to increase the foster care placement rate, which currently stands at around 20%, to 50%. In the midst of this trend, the foster care placement rate has been increasing year by year, but at the same time, there has been an upward trend in the cancellation of placement due to foster care breakdown.

According to the National Association of Child Guidance Centers (2011) “Survey on Foster Care and Abandoned Children in Child Guidance Centers”, the number of cases of termination of foster care placement during the five years from 2005 to 2009 was 647. Of these, 156 cases were terminated due to unsuccessful attempts, which accounted for approximately 24% of the total number of termination cases. In other words, one out of every four cases of termination of consignment was due to unsuccessful attempts.

In addition, it was shown that the background of the children who were released from consignment was often due to their behaviour and characteristics, such as indiscriminate attachment. In addition, the research team of the reporters conducted a national survey on measure changes in 2015. The results revealed that children with disabilities and children who had been abused accounted for a high percentage of children experiencing placement change, including those who were not in foster care. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clarify the actual situation and support needs of children who experienced the termination of consignment due to malfunctioning of foster carers, as well as the characteristics and trends in the process leading to malfunctioning of foster carers.

2. Perspectives and methods of research

A survey form was mailed to 605 children’s homes across Japan, asking them to respond to a questionnaire about “children who were newly admitted in the fiscal year 2019 as a ‘change of placements from foster carers’”. There are two types of questionnaires: the “Facility Questionnaire,” which asks respondents to provide an overview of the facility and the “Child Questionnaire,” a form to be filled out for each eligible child.

The Child Questionnaire consists of four main parts:

(1) The child’s situation at the time of admission;

(2) The situation of the foster carers who terminated the contract;

(3) The current situation of the subject child;

(4) The subject child’s checklist (ACEs, SDQ, well-being scale).

In this report, we present the results of the analysis conducted only on “the route of the change of placements for the child concerned” and “the basic attributes of the child concerned” among the contents of the “child questionnaire”. Respondents to the questionnaire and the type of job were left to the discretion of each facility. The survey period was from November 2020 to the end of January 2021.

3. Ethical considerations

This survey was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of the Graduate School of Human and Social Systems Sciences, Osaka Prefecture University (Approval No. 2020 (1)-26). Specifically, the survey request letter and consent form enclosed with the survey form explained that responses to the survey were voluntary, that care would be taken to ensure that individuals and regions would not be identified when the results were published, and that the management of data after the survey would be carried out.

4. Research results

- Number of children included in the analysis

- Of the 605 facilities to which questionnaires were mailed, responses were received from 262 facilities (collection rate: 43.3%). Of these, 58 facilities responded that “there were children who entered from foster care in FY 2019 due to a change in measures,” and a total of 107 children responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 99 child forms were included in the analysis after deleting eight cases that had incomplete responses.

- Attributes of the target children

- The gender of the children was 42 boys (42.4%) and 57 girls (57.6%). There were no children aged 0 and one, 27 (27.2%) were aged two to six, 37 (37.4%) were aged seven to 12, which corresponds to elementary school age, 24 (24.2%) were aged 13 to 15 (13 of them were aged 15), and 11 were aged 16 to 18. The age at which they first used social care was 0 years old for most of them 33 (33.3%). The age at which they were first placed to foster care was concentrated at two years (11 respondents, 11.1%) and three years (10 respondents, 10.1%). The most common reason for being placed to foster carers was the need for long-term care with no prospect of returning home (28 respondents, 28.3%), followed by the need for an attachment relationship with a specific adult (25 respondents, 25.3%).

- Circumstances that led to the failure of the foster carers

- Regarding whether or not the children had experienced abuse from their foster carers, psychological abuse was the most common type of abuse with 16 (16.2%) of the respondents, followed by physical abuse with 11 (11.1%).

- Number and route of measure changes experienced

- The most frequent placement changes experienced (including temporary protection, excluding respite) were four (39 39.4%), with an average of 4.88 and the most frequent being 11. Thirty-four children had been placed in infant homes, and of these, five had been in foster care for more than five years and 11 for less than one year. Of the 15 children who had been placed in foster care after having been returned home and placed in foster care multiple times, 12 had an ACEs score of five or more, and seven had the highest score of seven. All but one of the children (age nine) had been in foster care for more than five years. 20 children were 13 years old or older when they were first placed in foster care, and only three of these children had been in the care of that foster family for more than one year. 16 children had lived in the same institution for three years or more before being placed in foster care, but none of these children were 14 years old or older at the time of placement. Of these 16 children, three had been in foster care for more than three years.

5. Consideration

The results of the study suggest the need for the following:

- The need for foster carers’ support to overcome the fostering of adolescents due to a large number of breakdown and changes in placements at the age of puberty.

- Foster care for children over 13 years old and the necessity of supporting foster carers.

- Necessity of examining the placements to be taken for children who have experienced a return to their families.

- The need for careful discussions on the pros and cons of changing the placements of children who have lived in institutions for more than three years to foster carers.

- Necessity of re-examining the content and nature of foster carer recruitment and pre-registration training.

Research on Social Work for foster families

In Scotland, the UK, where the foster care commissioning rate is higher than in Japan, I am currently conducting several surveys to clarify how Social Work for foster families is developed and under what values, as well as the conflicts and challenges faced in practice.

For many years, social foster care in Japan has been developed mainly through institutional (residential) care. Japan has been recommended by the United Nations to improve its policies on social foster care, including the low rate of foster care placement. In addition to the shortage of foster carers, the recommendations for improvement include the fact that the institutional care system is too large to be considered “home-like.”

In response to international criticism and pressure, including recommendations from the United Nations, Japan has been promoting family care in social foster care. In August 2017, the Japanese government announced the “New Vision for Social Foster Care”, in which one of the goals is to increase the foster care placement rate from the current level of approximately 17% to 50%.

In addition, one of the goals of this “New Vision” is to establish a “fostering organisation” in each prefecture to support foster carers. The role of this fostering agency is “Social Work for foster families and children.” Social Work for foster families and children consists of various activities to support the appropriate process of foster care placement, and it is an “integrated practice of support for children, support for biological parents, and support for foster carers.”

The term and concept of “fostering” was introduced from the UK. The foster care placement rate in the UK is about 70%, which is more than three times higher than that in Japan. To promote foster care, we are trying to introduce the system of the UK, which can be said to be a leading country in foster care, but there is no concrete introduction of how this fostering agency functions in the UK.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the value and practice of Social Work for foster families and children based on the results of interviews with supervising workers, foster carers, and residential workers that care for children who have experienced disruption with their foster carers.

The results of the study revealed the following:

Attachment to the local area

In Japan, when a child is found to require social foster care, foster carers are sought within the local authority where the child lives, and if foster carers cannot be found within the local authority, the child is placed in an institution within the local authority. However, in Scotland, if no suitable foster carers can be found in the local authority, the child is placed with foster carers in another local authority.

This is due to the fact that the principle of the priority of family care for children is firmly adhered to, but this raises the issue of disconnection between the child and the local community. Consideration for children’s “attachment to the local area” is not taken into account as much as in Japan.

Foster case drift

In the UK, including Scotland, the problem of foster care drift is more serious than in Japan, and it is not uncommon for a child to experience more than ten different foster families before the age of ten.

Foster carers in Scotland are expected to ‘raise children in a loving family’, with the understanding of the child’s support needs and the skills and knowledge to respond to them being given a lower priority than love. Foster carers are not expected to be responsible for the care of children ‘as a job’, but to raise children ‘as a natural family’.

However, foster carers want to see more social recognition of the fact that they are foster carers as their “job” and that they play a “social role” as foster carers, and they expect rewards and recognition commensurate with the difficulty and importance of their role.

Children’s hearing

In Scotland, there is a system called “Children’s Hearing” to listen to the views of children. Children are guaranteed the opportunity to express their opinions on the content of their placements and how they should interact with their biological parents during the separation.

In addition to the social worker of the family placement team, the child is assigned to a panel of three people who listen to the child’s voice, and the panel plays the role of representing and reinforcing the child’s voice. However, due to the difficulty in coordinating the schedule of these three panels, it is difficult to make decisions promptly, and the role of the three panels in listening to the children’s voices has led to an emphasis on the “ability and role to objectively judge and assess the situation” as necessary for social workers in charge of children.

On the other hand, it was found that the skills of acceptance, empathy, and listening when confronting children as a social worker are becoming less important.

The future of foster care

The UK, including Scotland and England, has developed many excellent formats such as legal systems and guidelines for child and family welfare, including social foster care, and there is a growing movement in Japan to actively introduce these formats.

However, this study revealed that the current situation, where the existence of a good format does not necessarily mean that the practice is working well and that there are various operational challenges.

It is necessary to comprehensively understand and evaluate each of them from the three perspectives of macro, mezzo, and micro, such as the wonderful philosophy and the legal system developed based on it (macro), the system of local authorities and organisations that can appropriately operate it (mezzo), and the conflicts and actual condition of individual social workers who actually practice in these systems (micro). In this study, it became clear again that it is necessary to understand and evaluate each of them comprehensively and from a bird’s eye view, and then consider how to introduce them to Japan.

Social welfare research: Foster care support

Since April 2021, I have been a visiting researcher at the University of Glasgow, where I am conducting research on social work to prevent foster care breakdown. By way of background to my study, it’s important to say that the United Nations has many times now, recommended that improvement is needed in the Japanese social foster care system. The five main points concerning their recommendations are as follows.

1) The lack of ‘home-based care’ (foster care and adoption).

2) The mainstream of institutional care has been a ‘Large Building System’.

3) Group care in ‘infant home’ (for those between 0-2 years old).

4) The number of children handled by each social worker in Child Guidance Centres should be reduced.

5) A system should be created where children in and out of care express their views and let their voices be heard.

In response to the UN recommendations for improvement, Japan has been reforming its social foster care system since 2011. Specifically, this means “shifting from institutional care to home-based care,” and Japan has been promoting foster care by setting a high foster care placement rate as a goal.

However, as the rate of foster care placements has increased, so has the number of cases that lead to foster care breakdown. What is the background to this? One possible reason is that the number of foster parents has increased, and the number of children placed to foster families has increased without improving the support system for foster families.

The purpose of my study

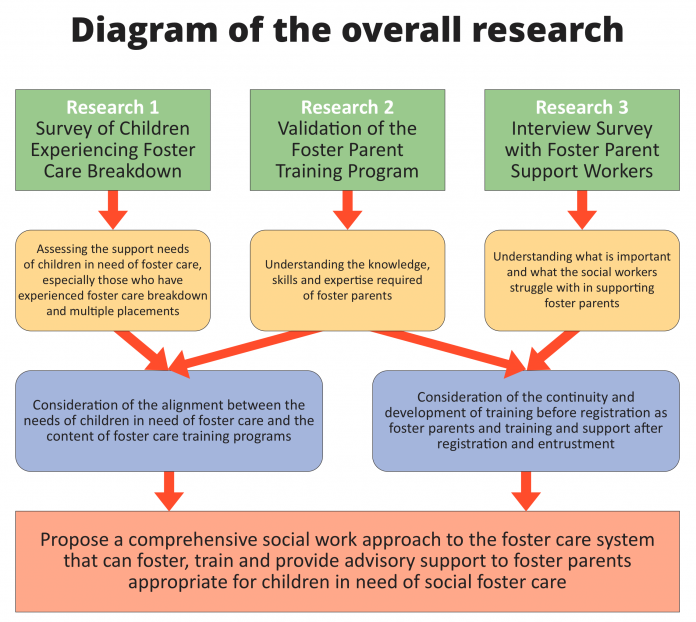

Based on my awareness of the above issues, I am currently conducting a research project intending to clarify the following four things.

1) Support the needs of children who need foster care.

2) Qualities and conditions of foster parents who can meet the support needs of children.

3) Training programme for foster parents who are capable of raising foster children appropriately.

4) Comprehensive social work for foster carers to support stable foster care.

Research methods

I am currently conducting the following four surveys.

1) A survey on the support needs of children who have experienced a change of placement to an institution in Japan due to the breakdown of foster care.

In FY2019, I conducted a fact-finding survey of 107 children who were changed to institutional care due to foster care breakdown in Japan (ACEs, SDQ, age, gender, pathway, etc.)

The results of the study revealed that children who had experienced foster care breakdown had much higher scores on both the ACEs and the SDQ than children who had not and that they had multiple serious behavioural and emotional problems. At this stage, it is not possible to determine causality as to whether these problems began before the children were placed in foster care, or whether they arose after the children were placed in foster care or as a result of their experience of poor foster care. One thing that can be said, however, is that the care needs of children who experience foster care problems and are transferred to institutions are very high, and institutions need to provide specialised care and treatment.

2) A comparative study between Japan and Scotland on the support needs of children who have experienced multiple changes of placement due to foster care breakdown.

Using the framework of the above survey, I would like to conduct a comparative study with children in Scotland who have experienced foster care breakdown and clarify the support needs of children who have experienced foster care breakdown.

In Scotland, children under the age of 13 are not placed in institutions rather than foster care, so I plan to exclude children under the age of 13 from the sample for the Japanese survey and compare the results between the two. At this stage, I know that looked-after children in Scotland experience more changes in placement than children in Japan. Unsurprisingly, children who change placements more frequently are more severely damaged. I believe that I can grasp some significant suggestions for Japan from the support needs of children who have experienced a change of placement in Scotland and the way residential care is provided in Scotland.

3) Review of the foster parent training program in Scotland

There are several foster care training programmes in Scotland, past and present. For example, “Skills to foster” and “Head, Heart, Hands Project” are examples of such programs. There are also several private foster parent support organisations in Scotland, each of which is believed to provide original foster parent support programmes.

At present, there are very few private foster parent support organisations in Japan, and public organisations are currently playing the caring roles. However, the Japanese government is planning to establish private fostering agencies in each municipality and to develop a support system for foster parents in each region.

Therefore, I would like to obtain hints from the Scottish practice to establish a comprehensive foster parent support system in each region, including recruitment, training, and visit support in Japan.

4) Interviews with foster care social workers & qualitative analysis

I am planning to elicit and qualitatively analyse what foster care support workers value in their practice and exploring the components of foster care social work in Scotland.